Is Sugar Poison? Understanding the Real Impact on Health

Understanding "Poison" in Nutritional Context

Defining Poison in Everyday Items

When we talk about poison in the context of everyday items, the term is much more nuanced than it appears. Take acetaminophen, commonly known as Tylenol. In appropriate doses, it's a go-to for relieving pain and fever, but take 20 times the recommended dose, and it becomes acutely toxic, leading to severe liver damage or even death. This dichotomy illustrates how even seemingly benign substances can turn dangerous when misused.

To further underscore this point:

- Appropriate Dose: 500-1000 milligrams every 4-6 hours.

- Dangerous Dose: 20 grams (20,000 milligrams) can lead to liver failure within days.

Alcohol provides another compelling example. In moderation, a glass of wine might even offer some health benefits, like improved heart health. Yet, in excessive quantities, alcohol becomes neurotoxic, damaging the brain and liver. This variability underscores an important point: the effect of a substance often hinges on the dose, frequency, and context of its use.

Sugar as Poison: Myth or Fact?

Labeling sugar as poison is an emotionally charged and overly simplistic view. It's a phrase that resonates more with fear than with scientific understanding. To assert that sugar is outright poison without considering dose and context is both misleading and unhelpful. Instead, we should ask about the biochemical impacts of different types of sugar, such as sucrose and fructose, under various conditions.

To break it down:

- Types of Sugars: Sucrose, Fructose, Glucose.

- Metabolic Pathways: Each sugar type is metabolized differently, affecting the body uniquely.

When examined closely, there’s insufficient evidence to suggest that sugar, when consumed in moderation and as part of a balanced diet, is inherently harmful. However, this doesn't imply that unrestricted sugar consumption is without consequences. Particularly for individuals with metabolic vulnerabilities, excessive sugar intake can drive overeating and contribute to weight gain and other health issues.

Biochemical Effects of Sugar

Different Types of Sugars

Understanding the biochemical effects of sugar begins with differentiating its various forms. Sucrose, commonly found in table sugar, and high fructose corn syrup, often used in processed foods and beverages, are just two types of sugar. Each has a unique metabolic pathway in the body, affecting insulin levels, energy storage, and appetite differently.

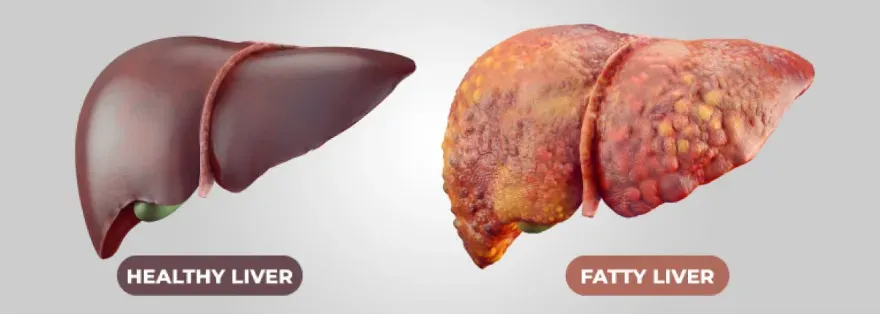

Fructose, in particular, is often scrutinized for its role in health. Unlike glucose, which is directly used by our cells for energy, fructose is primarily metabolized in the liver. Excessive consumption of fructose, especially in liquid form like sodas, can overwhelm the liver and may contribute to insulin resistance and fatty liver disease over time.

Key differences include:

- Sucrose: A disaccharide composed of glucose and fructose.

- High Fructose Corn Syrup: A mix of glucose and fructose in varying proportions.

- Fructose: Metabolized almost exclusively in the liver.

The Impact of Sugar on Metabolism

Sugar's impact on metabolism is multifaceted. For instance, when fructose is consumed in large quantities, especially in sugary drinks, it can promote overeating by failing to trigger the same satiety signals in the brain as glucose. This can lead to increased caloric intake and weight gain. However, studies show that when total energy intake is controlled, replacing glucose with fructose doesn’t necessarily worsen health outcomes.

In more detail:

- Satiety Signals: Fructose doesn't promote the release of insulin and leptin as effectively as glucose, leading to reduced satiety.

- Caloric Intake: Excessive fructose can drive up total caloric consumption, especially in liquid forms.

A robust experiment involving mice, where their calorie intake was meticulously controlled over nine months, demonstrated no significant difference in body weight between high and low fructose groups. This suggests that the dose and metabolic context are critical factors in determining sugar’s health impact.

Further implications include:

- Controlled Studies: Experiments show no significant metabolic detriment under controlled caloric conditions.

- Real-world Application: In free-living environments, sugar consumption often leads to higher total caloric intake.

Sugar Consumption in Various Contexts

Sugar and Physical Activity

The context of sugar consumption significantly affects its impact. In highly active individuals, like those training intensely, sugar serves as a vital quick-energy source. Consider an anecdote from a teenage athlete training six hours a day, consuming up to 200 grams of sugar daily without adverse health effects. The high level of physical activity offset the high sugar intake, leading to a lean body with minimal fat.

For such individuals, sugar helps:

- Replenish Glycogen Stores: Essential for sustained performance and recovery.

- Provide Quick Energy: Vital for maintaining high levels of physical activity.

Thus, in an active lifestyle, sugar's quick-release energy is utilized efficiently, minimizing its potential negative effects. Moreover, such high levels of physical activity create a metabolic environment where sugar is less likely to cause harm.

Sugar in a Sedentary Lifestyle

Conversely, in a sedentary lifestyle, high sugar intake becomes problematic. Without the offsetting factor of regular physical activity, excess sugar is more likely to be stored as fat, leading to weight gain and metabolic disturbances. Modern dietary patterns, which often include high quantities of sugary beverages and processed foods, exacerbate this issue.

Consider these points:

- Caloric Surplus: Excess sugar without corresponding activity leads to weight gain.

- Metabolic Disturbances: Increased risk of insulin resistance and inflammation.

Overconsumption of sugar in a sedentary context can drive insulin resistance, inflammation, and a host of other metabolic issues. Therefore, understanding the context in which sugar is consumed is crucial for making informed dietary choices. Adopting a more active lifestyle can help mitigate some of the negative effects associated with high sugar intake.

The Role of Fructose in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

Mechanistic Data vs. Clinical Evidence

Fructose's role in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a hot topic in nutritional science. Mechanistic data suggest that fructose, especially in liquid form, might exacerbate NAFLD more than glucose. The liver's metabolism of fructose can lead to fat accumulation, inflammation, and insulin resistance, key factors in NAFLD progression.

Key Mechanisms:

- Liver Metabolism: Fructose is metabolized in the liver, promoting fat accumulation.

- Inflammation and Insulin Resistance: Chronic fructose consumption can lead to systemic inflammation.

However, while mechanistic data is compelling, clinical evidence remains sparse. We still lack definitive clinical trials showing that an isocaloric substitution of fructose with glucose improves NAFLD outcomes independently of weight loss. Thus, while there is a theoretical basis for reducing fructose intake in NAFLD patients, robust clinical trials are needed for conclusive evidence.

Further Considerations:

- Clinical Trials: More research needed to confirm mechanistic hypotheses.

- Weight Loss: Primary intervention for NAFLD remains weight loss through caloric restriction.

The Role of Liquid Fructose

Liquid fructose, such as that found in sugary drinks, is particularly concerning. Its rapid absorption can lead to spikes in blood sugar and insulin levels, promoting fat storage in the liver. Emerging research suggests that liquid fructose could play a more significant role in the development of NAFLD compared to its solid counterparts.

Consider these aspects:

- Rapid Absorption: Liquid fructose leads to quick spikes in blood sugar and insulin.

- Fat Storage: Increased likelihood of promoting fat storage in the liver.

Given these potential risks, reducing liquid fructose intake is a prudent approach, especially for those at risk of or managing NAFLD. While clinical trials continue to explore these hypotheses, current recommendations often emphasize avoiding sugary beverages to mitigate potential harm. Substituting these with water, herbal teas, or naturally flavored water can be a healthier choice.

Practical Approaches to Sugar Intake

Personalized Recommendations

Personalized dietary recommendations are essential when it comes to managing sugar intake. For individuals who are metabolically healthy, moderate sugar consumption, particularly from whole foods like fruits, is typically not problematic. These individuals can afford some flexibility without significant health repercussions.

Personalized advice can include:

- Moderate Consumption: Whole fruits as primary sugar sources.

- Flexibility: Occasional indulgence without adverse effects.

However, for those who are metabolically unhealthy, strict regulation of sugar intake is advisable. This includes reducing not just fructose but also overall added sugars to improve metabolic markers and support weight loss. Tailoring sugar intake based on individual metabolic health helps optimize outcomes and prevents the negative impact of excessive sugar consumption.

Moderation and Dietary Patterns

Moderation and overall dietary patterns are key when considering sugar intake. Emphasizing whole foods, like fruits, that naturally contain sugar but also provide fiber, vitamins, and minerals, can be a healthy approach. Reducing intake of sugary beverages and processed foods, which are often devoid of nutritional value, helps maintain metabolic health.

Key Strategies:

- Whole Foods: Prioritize fruits and vegetables.

- Limit Sugary Beverages: Opt for water, herbal teas, or naturally flavored waters.

For those who enjoy the occasional sweet treat or sugary drink, keeping these indulgences infrequent can mitigate potential harm. A balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains, coupled with regular physical activity, forms the foundation of a healthy lifestyle where sugar can be enjoyed in moderation.

Holistic View on Nutrition and Health

The 2x2 Framework for Assessing Nutritional Needs

A holistic view of nutrition considers more than just sugar intake. A useful framework for assessing nutritional needs looks at whether an individual is overnourished or undernourished, indicated by body fat levels, and whether they are adequately muscled or underused, determined by fat-free mass index or appendicular lean mass index.

Framework Components:

- Overnourished vs. Undernourished: Body fat and visceral fat assessments.

- Adequately Muscled vs. Underused: Fat-free mass and appendicular lean mass indexes.

Additionally, assessing metabolic health is crucial. By understanding these factors, health professionals can craft personalized nutrition and training plans that address an individual's specific needs, ensuring balanced and effective health management. This approach allows for targeted interventions that optimize overall health and well-being.

Overnourished vs. Undernourished

Understanding whether a person is overnourished or undernourished goes beyond simple calorie counting. It involves evaluating body composition, fat distribution, and muscle mass. Overnourished individuals may have excess body fat but still be nutrient-deficient, while undernourished individuals may lack sufficient muscle mass despite a seemingly adequate diet.

Consider these points:

- Body Composition: Evaluation of fat and muscle distribution.

- Nutrient Deficiency: Potential issue even in overnourished individuals.

This nuanced approach allows for more targeted interventions. For instance, overnourished individuals may benefit from reducing caloric intake and increasing physical activity, while undernourished individuals might need nutrient-dense diets to build muscle and improve overall health. This personalized strategy helps achieve optimal health outcomes tailored to individual needs, ensuring a balanced and sustainable approach to nutrition and fitness.