The Complete Guide to Chronic Health Conditions and Disease Prevention

Key takeaways

- Chronic conditions develop gradually through long-term system strain.

- Metabolic health is a central driver of disease risk.

- Chronic inflammation accelerates disease progression.

- Lifestyle changes address root mechanisms, not just symptoms.

- Medical care and prevention work best when integrated.

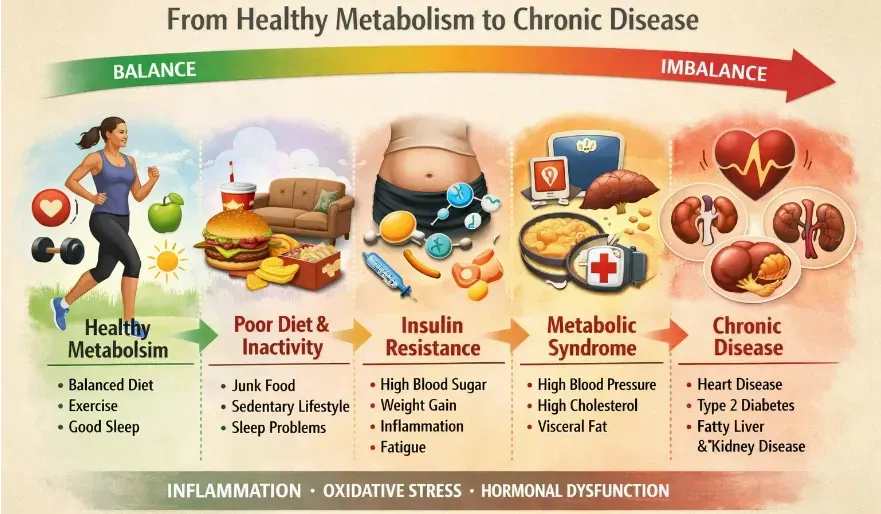

Understanding chronic disease requires moving beyond labels and diagnoses and into systems. Metabolism, inflammation, lifestyle patterns, stress exposure, and environmental inputs all interact to shape disease risk. This guide explains how chronic conditions form, why they persist, and how prevention works at a biological and behavioral level.

Rather than focusing on any single disease, this article provides a framework that applies broadly across conditions — helping readers understand why prevention works and where it has the greatest leverage.

What Makes a Condition “Chronic” vs. Acute

Acute conditions are defined by their short duration and clear resolution. Infections, injuries, and sudden inflammatory responses typically fall into this category. The body identifies a threat, mounts a response, and — with or without medical support — returns to baseline.What distinguishes chronic disease is not constant symptoms, but persistent underlying drivers. Symptoms may improve or worsen, but the biological processes fueling the condition remain active unless intentionally addressed.

Why Chronic Disease Develops Gradually

Most chronic conditions begin long before symptoms appear. The early stages often involve subtle shifts in metabolic function, immune signaling, or tissue repair. These changes are easy to overlook because they rarely cause immediate discomfort.Metabolic Health as the Foundation of Chronic Disease

Metabolic health describes how effectively the body manages energy: regulating blood glucose, lipids, hormones, and fuel use across tissues. When metabolic systems function well, cells receive energy efficiently and inflammation remains controlled.Importantly, metabolic dysfunction is not synonymous with obesity. People at many body sizes can experience impaired insulin sensitivity, fatty liver, or dyslipidemia. Chronic disease risk is tied to metabolic state, not appearance.

How Insulin Resistance Increases Disease Risk

When insulin signaling is impaired, the body shifts into a compensatory mode. Elevated insulin promotes fat storage, suppresses fat breakdown, and alters lipid metabolism. Over time, this contributes to vascular damage, increased blood pressure, and systemic inflammation.Inflammation: A Necessary Process That Becomes Harmful

Inflammation is not inherently bad. Acute inflammation is a protective immune response that helps heal injuries and fight infections. Once the threat resolves, inflammatory signaling normally subsides.Drivers of Chronic Inflammatory Load

Low-grade inflammation is influenced by multiple overlapping factors:- Persistent metabolic dysfunction

- Diets high in ultra-processed foods

- Physical inactivity

- Chronic psychological stress

- Inadequate sleep and circadian disruption

Reducing inflammation is less about eliminating a single trigger and more about lowering the total inflammatory burden.

Lifestyle Patterns as Primary Prevention Tools

Lifestyle factors directly shape metabolic and inflammatory pathways. Nutrition influences glucose control and immune signaling. Physical activity improves insulin sensitivity and vascular health. Sleep regulates hormones that control appetite, stress, and repair.Nutrition’s Role in Chronic Disease Prevention

Diet influences disease risk through multiple mechanisms: nutrient sufficiency, glucose regulation, inflammation, and gut microbiome composition. Whole-food–based eating patterns tend to support metabolic stability and immune balance.Physical Activity as a System Regulator

Movement improves health far beyond calorie expenditure. Muscle contractions increase glucose uptake independent of insulin, reducing blood sugar levels. Cardiovascular activity improves oxygen delivery and vascular function.Regular physical activity also lowers baseline inflammation, improves lipid profiles, and supports cognitive health. Importantly, exercise acts as a signal — telling the body to preserve muscle, bone, and metabolic capacity.

Sleep, Stress, and Nervous System Health

Sleep deprivation and chronic stress disrupt hormonal regulation. Cortisol remains elevated, appetite hormones become dysregulated, and inflammatory signaling increases. These effects compound metabolic dysfunction.Lifestyle Changes vs. Medication: Understanding Their Roles

Medications are critical tools for managing chronic disease, especially when risk is high or damage is advanced. Blood pressure medications, glucose-lowering agents, lipid-lowering drugs, and anti-inflammatory therapies reduce complications and save lives.When Medical Care Is Essential

Prevention does not mean avoiding healthcare. Screening, monitoring, and early intervention are essential components of disease prevention. Many chronic conditions are most manageable when identified early.The Long View: Prevention as a Process

Chronic disease prevention is not a single decision or phase of life. It’s an ongoing process shaped by habits, environments, and access to care. Progress is rarely linear, and setbacks are part of the process.What matters most is direction. Small, consistent improvements compound over time. Systems respond gradually — but they do respond.

Why “Complete” Means Systemic, Not Exhaustive

No single article can list every chronic condition or prevention strategy. A complete guide provides a framework — a way to understand how diseases develop and where intervention is most effective.

Related Health Conditions and Disease Topics

- How to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes

- 10 Science-Backed Habits That Cut Cancer Risk

- Understanding and Preventing Cavities

- Understanding Atherosclerosis

References:

1. CDC — Chronic Disease Overview & Prevention Strategies

- https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/prevention/index.html

- Regular physical activity, healthy eating, and other lifestyle behaviors help prevent or manage chronic diseases.

2. CDC — Preventing Chronic Disease (Public Health Journal)

- https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/index.htm

- A comprehensive CDC resource detailing public health research and strategies for chronic disease prevention.

3. Cleveland Clinic — Metabolic Syndrome Explained

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/10783-metabolic-syndrome

- Describes metabolic syndrome, its risk factors, and how it increases the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

4. PMC — Lifestyle, Inflammation & Insulin Resistance

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10857191/

- Explores how lifestyle factors like diet and physical activity are linked to insulin resistance and inflammation.

5. CDC — Metabolic Syndrome Risk Across Weight Categories

- https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2020/20_0020.htm

- Shows metabolic syndrome increases mortality risk even in normal-weight adults, highlighting metabolic health over appearance.

6. Wikipedia — Ultra-processed Food and Type 2 Diabetes Risk

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ultra-processed_food

- Explains how higher consumption of ultra-processed foods is linked to increased risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

7. Wikipedia — Diabesity (Obesity + Diabetes Relationship)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diabesity

- Defines the combined burden of obesity and type 2 diabetes and how lifestyle factors contribute to metabolic disease risk.

8. Scientific Article — Inflammation, Physical Activity, and Chronic Disease

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666337620300081

- Shows exercise and weight loss reduce low-grade inflammation and lower chronic disease risk.